What Are the Key Factors That Determine the Cost of a Fully Automatic Filter Press?

2026.02.09

2026.02.09

Industry News

Industry News

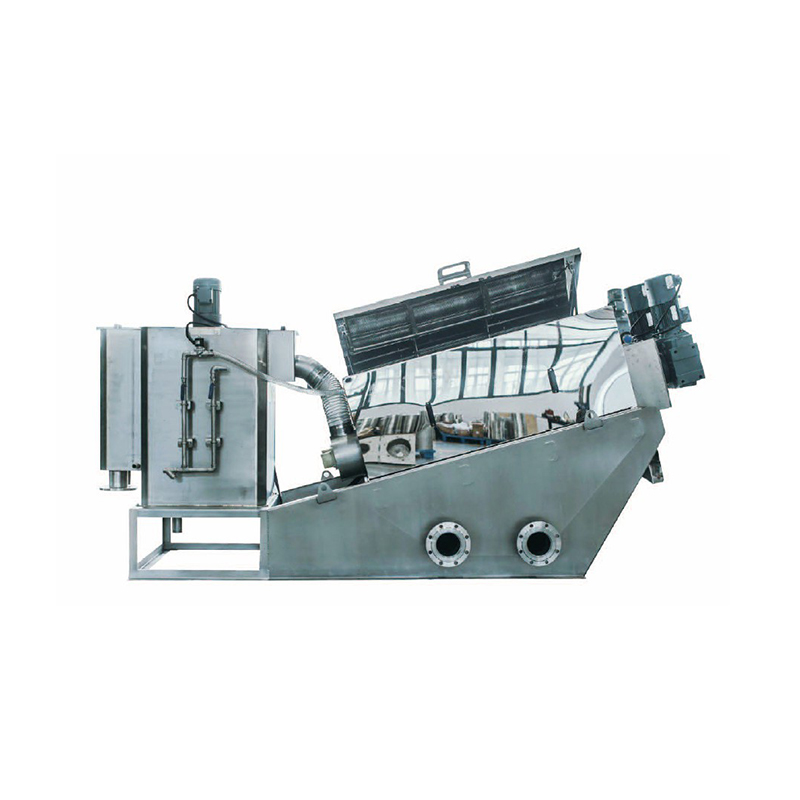

For industrial operations ranging from mining and chemical processing to municipal wastewater treatment, investing in a fully automatic filter press is a strategic move toward operational efficiency and reduced labor costs. However, when requesting quotes, many project managers find a significant price variance between models that seemingly “do the same thing.”

The cost of a filter press is not just a reflection of its physical size; it is a complex calculation of material science, engineering precision, and automation depth. Understanding these cost drivers is essential for calculating your Return on Investment (ROI) and Total Cost of Ownership (TCO).

1. Filtration Area and Volume: The Scale of Production

The most immediate driver of cost is the physical scale of the machine, measured by the filtration area () and the cake volume. This dictates how much solid material the machine can process in a single cycle.

- Plate Quantity and Size:A system with 500mm x 500mm plates costs significantly less than a 2000mm x 2000mm mammoth. Each increase in plate size requires the main frame (side rails or bridge beams) to be exponentially reinforced. To withstand massive hydraulic clamping forces—often reaching hundreds of tons—large-scale machines require thicker, higher-grade high-tensile carbon steel.

- Structural Integrity and Material Consumption:As the filtration area increases, the mechanical stress on the frame grows. Fully automatic large-scale presses often require complex welding processes and expensive anti-corrosion treatments, such as sandblasting followed by epoxy zinc-rich coatings. In corrosive environments, the frame may even require stainless steel cladding. The raw material costs and processing labor for this heavy steel skeleton constitute a major portion of the initial investment.

- Throughput Capacity:Choosing a size isn’t just about meeting current needs but handling peak flows. A system designed to handle a higher dry solids rate per hour (DS/h) requires more robust support components and faster cycle times, which naturally commands a higher price point.

2. Degree of Automation: From Basic Cycles to “Lights-Out” Operation

The term “automatic” exists on a spectrum. The closer you move toward a “lights-out” or autonomous factory environment, the higher the upfront capital expenditure (CAPEX), but the lower the long-term operating expenditure (OPEX).

- Plate Shifting Systems:A basic automatic press might shift one plate at a time. High-end “Fast Action” models can shift groups of plates or even the entire plate pack simultaneously (one-time discharge) to drastically reduce cycle time. This requires complex mechanical linkages, variable frequency drive (VFD) motors, and high-precision displacement sensors.

- Integrated Control Systems (PLC):The “brain” of the machine—usually a Siemens or Allen-Bradley PLC—is a core cost driver. Advanced systems include SCADA integration, remote monitoring via the Internet of Things (IoT), and automated pressure compensation. These systems allow the press to “think,” adjusting feed pump speeds based on internal pressure sensor feedback to optimize cake dryness and prevent “blowouts.”

- Ancillary Robotics:Features like automatic cloth washing systems, automatic drip trays (bomb-bay doors), and cake discharge vibrators are modular additions. While they increase the initial purchase price, they eliminate the need for manual intervention, significantly reducing the risk of operator injury and increasing the effective uptime of the equipment.

3. Cost Comparison Table: Manual vs. Fully Automatic Filter Press

|

Cost Dimension |

Manual/Semi-Automatic |

Fully Automatic Filter Press |

Long-term Impact |

|

Initial Capital (CAPEX) |

Low to Medium |

High Initial Investment |

Significant premium for automation technology. |

|

Labor Cost (OPEX) |

Very High (Requires manual discharge) |

Very Low (Periodic supervision only) |

Automation typically pays for itself within 12–24 months via labor savings. |

|

Cycle Efficiency |

Highly Variable (Operator dependent) |

High (PLC precision control) |

Ensures consistent cake dryness and production stability. |

|

Maintenance Depth |

Simple Mechanical |

Specialized Technical |

Automated systems require tech-savvy electrical/hydraulic maintenance. |

|

Safety Systems |

Basic Protection |

Advanced (Light curtains, interlocks) |

Significantly reduces accident risks and legal liability. |

4. Materials of Construction: Chemical Compatibility and Pressure

The physical environment in which the filter press operates dictates the grade of materials used, which plays a pivotal role in the cost structure.

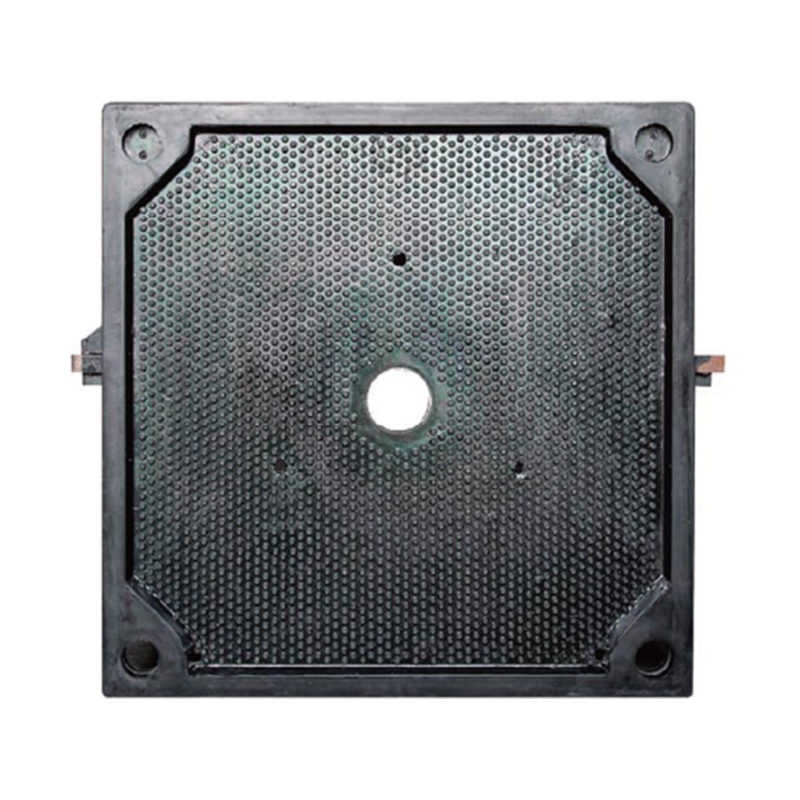

- Filter Plate Material:Most standard plates are made of reinforced polypropylene (PP). However, if your process involves high temperatures () or extreme chemical acidity/alkalinity, you may require specialized PVDF or even cast iron/stainless steel plates. These specialized plates can cost 3 to 5 times more than standard PP plates.

- Membrane Squeezing Technology:A Membrane Filter Press is considerably more expensive than a standard chamber press. It includes flexible, expandable membranes that allow for a “secondary squeeze” of the filter cake. This adds the cost of an auxiliary air or high-pressure water inflation system but yields significantly drier cakes, which drastically reduces subsequent sludge disposal and transportation fees.

- Corrosion Protection Grade:In harsh environments (such as battery recycling or mining), the entire frame may need to be clad in 304 or 316 Stainless Steel. This protection ensures the machine does not corrode away in an acidic atmosphere, but it represents a massive leap in material costs.

5. Hydraulic and Pumping Systems: The Power Behind the Press

A filter press is only as efficient as the pressure it can maintain. The engineering behind the hydraulic power unit (HPU) and the feed pump is a major pricing variable.

- High-Pressure Capabilities:Standard presses operate at 6–8 bar. High-pressure models (15–20 bar) require thicker plate edges and massive hydraulic cylinders. Moving from standard to high pressure involves a qualitative jump in mechanical strength and component weight, leading to a surge in costs.

- Feed Pump Integration:Many suppliers quote only the machine itself, but a true “Fully Automatic System” usually includes a coordinated feed pump (such as a pneumatic diaphragm, screw, or specialized filter press pump). Integrating the pump logic into the PLC ensures the press is not over-pressurized, protecting the filter cloths and preventing “spraying” or frame misalignment.

- Hydraulic Reliability:Premium systems use high-cycle valve blocks and heavy-duty seals. In an automatic environment where the machine may cycle 20+ times a day, the cost of high-reliability hydraulic components is essentially an insurance policy against unplanned downtime.

FAQ: Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Is a fully automatic filter press worth the extra cost over a manual one?

A: If your labor costs are high or your production volume is consistent and large, yes. The ROI is usually realized quickly through labor savings, increased capacity, and the “Dry Cake” benefit, which lowers transportation and landfill fees.

Q2: How does cake dryness affect the overall cost?

A: While a machine that produces a drier cake (like a membrane press) costs more initially, it can save thousands of dollars annually in waste disposal costs. In many industries, “shipping water” to a landfill is the single largest hidden expense.

Q3: Can I upgrade a manual filter press to be automatic later?

A: While some components can be retrofitted, it is rarely cost-effective. The frame of an automatic press is designed from the ground up to accommodate shifting tracks and sensors. It is almost always better to invest in the level of automation you will need three years from now.

References & Further Reading

- Water Environment Federation (WEF):Guidelines for automated sludge dewatering systems and cost-benefit analysis.

- Chemical Engineering Journal:Studies on energy efficiency in high-pressure membrane filtration vs. standard chamber presses.

- ISO 9001:2015 Standards:Quality management systems in the manufacturing of industrial pressure vessels and filtration equipment.

English

English Español

Español हिंदी

हिंदी Tiếng Việt

Tiếng Việt